"The Flying Saucer"

The Application of the Biefield-Brown Effect

to the Solution of the Problems of Space Navigation

(Return to Index Page)

by Mason Rose, Ph.D., President

University for Social Research (1952)

Published in Science and Invention, August 1929, and

Psychic Observer, Vol. XXXVII, No. 1

by Gaston Burridge

American Mercury

June, 1958

The scientist and layman alike encounter a primary difficulty in

understanding the

Biefeld-Brown Effect and it's relation

to the solution of the flying saucer mystery.

A proper interpretation of this theory is prevented because both

scientist and layman are conditioned to think in electromagnetic

concepts, whereas the

Biefeld-Brown effect relates to

electrogravitation.

Their lack of awareness is justifiable, however, because the data

on electrogravitation, inasmuch as it is a comparatively recent

and unpublished development, has limited availability and

circulation. Townsend Brown, the discoverer of

electrogravitational coupling, is the only known experimental

scientist in this new area of scientific development as of this

writing. Thus, anyone wanting to understand electrogravitation

and its applications to astronautics must dismiss the principles

of electromagnetics in order to grasp the essentially different

principles of electrogravitation. Electrogravitational effects do

not obey the known principles of electromagnetism.

Electrogravitation must be understood as an entirely new field

of scientific investigation and technical development.

The most efficient method of effecting an understanding of

electrogravitation is to review the evolutionary development of

electromagnetism.

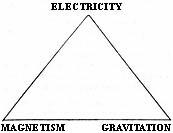

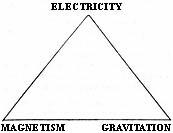

From the smallest atom to the largest galaxy, the universe

operates on three basic forces, namely

Electricity, Magnetism

and Gravitation. These forces can be represented as

follows:

Taken separately, these forces are of no real practical use.

Electricity by itself is static electricity and therefore

functionless. It will make your hair stand on end, but that is

about all.

Magnetism by itself has very few practical applications aside

from the magnetic compass, and gravity simply keeps objects and

people pinned to the earth.

However, when they are used to work in combination with each

other, almost endless technical applications come into being.

Currently, our total electrical development is based on the

coupling of electricity with magnetism, which provides the basis

for the countless uses we make of electricity in modern

societies.

Faraday conducted the first productive empirical experiment with

electromagnetism around 1830, and Maxwell did the basic

theoretical work in 1865.

The application of electromagnetism to microscopic and

sub-microscopic particles was accomplished by Max Planck's work

in quantum physics about 1890; and then in 1905 Einstein came

forward with relativity, which dealt with gravitation as applied

to celestial bodies and universal mechanics.

It is principally out of the work of these four great scientists

that our electrical developments, ranging from the simple

lightbulb to the complexities of nuclear physics, have

emerged.

In 1923, Dr. Biefield, Professor of Physics and Astronomy at

Dennison University and a former classmate of Einstein in

Switzerland, suggested to his protoge, Townsend Brown, certain

experiments which led to the discovery of the Biefield-Brown

effect, and ultimately to the electrogravitational energy

spectrum (in actuality, it was Brown who first observed the

effect and brought it to the attention of Dr. Biefield, who

suggest further experiments to determine the origin of and

enhance the effect - Juniper).

Biefeld wondered if an

electrical condenser, hung by a thread, would have a tendency to

move when it was given a heavy electrical charge. Townsend Brown

provided the answer. There is such a tendency.

After 28 years of investigation by Brown into the coupling effect

between electricity and gravitation,

it was found that for

each electromagnetic phenomenon there exists an

electrogravitational analogue. This means, from the technical

and commercial viewpoint, potentialities for future development

and exploitation are as great or greater than the present

electrical industry. When one considers that electromagnetism is

basic to the telephone, telegraph, radio, television, radar,

electric generators and motors, power production and

distribution, and is an indispensable adjunct to transportation

of all kinds, one can see that the possibility of a parallel, but

different development in electrogravitation has almost unlimited

prospects.

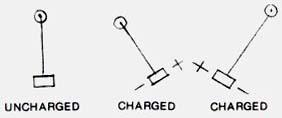

The initial experiments conducted by Townsend Brown, concerning

the behavior of a condenser when charged with electricity, had

the characteristic of simplicity which has marked most other

great scientific advancements.

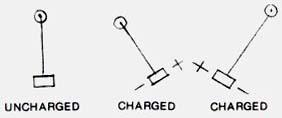

The first startling revelation was that if placed in free

suspension with the poles horizontal, the condenser, when

charged, exhibited a forward thrust toward the positive poles. A

reversal of polarity caused a reversal of the direction of

thrust. The experiment was set up as follows:

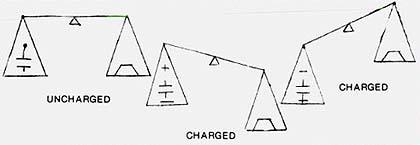

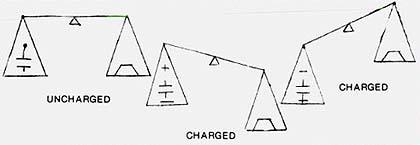

The antigravity effect of vertical thrust is demonstrated by

balancing a condenser on a beam balance and then charging it.

After charging, if the positive pole is pointed upward, the

condenser moves up.

If the charge is reversed and the positive pole pointed downward,

the condenser thrusts down. The experiment is conducted as

follows:

These two simple experiments demonstrate what is now known as the

Biefeld-Brown effect. It is the first and, to the best of

our knowledge, the only method of affecting a gravitational field

by electrical means. It contains the seeds of control of gravity

by man. The intensity of the effects is determined by five

factors, which are:

It is this fifth point which is inexplicable from the

electromagnetic viewpoint and which provides the connection with

gravitation.

On the basis of further experimental work from 1923 to 1926;

Townsend Brown in 1926, described what he called a "space car."

This was a revolutionary method of terrestrial and

extra-terrestrial flight, presented for experiment while motor

propelled planes were yet in a primitive stage.

This engineering feat by Townsend Brown was all the more

remarkable when we consider such a machine produces thrust with

no moving parts, does not use any aerodynamic principles of

flight, and has neither control surfaces, or a propeller.

Townsend Brown had discovered the secret of how the flying

saucers fly years before and such objects were reported.

Now the basic differences between electromagnetism and

electrogravity have been described and the basic principles of

the Biefield-Brown effect have been outlined, we are finally

ready to understand the principles of astronautics or the

conquest of space.

The earth creates and is surrounded with a gravitational field

which approaches zero as we go far into space. This field presses

objects and people to the earth's surface; hence it presses a

saucer object to the earth.

However, through the utilization of the Biefield-Brown effect,

the flying saucer can generate an electrogravitational field of

its own which modifies the earth's field.

This field acts like a wave, with the negative pole at the top of

the wave and the positive pole at the bottom, the saucer travels

like a surfboard on the incline of a wave that is kept

continuously moving by the saucer's electrogravitational

generator.

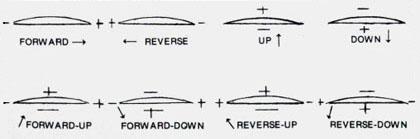

Since the orientation of the field can be controlled, the saucer

can thus travel on its own continuously generated wave in any

desired angle or direction of flight.

Since the saucer always moves towards its positive pole, the

control of the saucer is accomplished by varying the orientation

of the positive charge. Control, therefore, is gained by

switching charges rather than by the control surfaces. Since the

saucer is traveling on the incline of a continually moving wave

which it generates to modify the earth's gravitational field, no

mechanical propulsion is necessary.

Once we understand that the horizontal and vertical controls are

obtained by shifting the positive pole which turns the field,

then we are in a position to extrapolate a finished saucer

design.

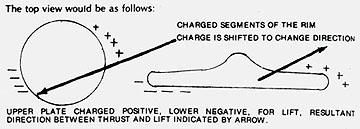

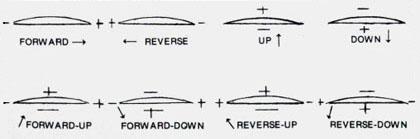

The method of controlling the flight of the saucer is illustrated

by the following simple diagrams showing the charge variations

necessary to accomplish all directions of flight.

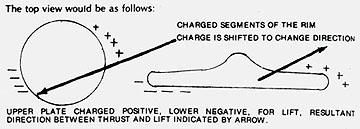

The saucer's edge would contain a number of conductor segments,

and the saucer would turn in any direction simply by shifting the

positive and negative charges to appropriate positions along its

edge.

The vertical thrust would be regulated by varying the charge

on top of the saucer, the amount of thrust being regulated by the

amount of charge generated.

In all probability, flying saucers do not utilize external

controls for direction, nor do they have any visible means of

propulsion. Flying saucers travel using the Biefield-Brown

electrogravitational effect, and hence do not utilize any of the

standard aerodynamic principles of an airfoil. Flying saucers

cannot be understood from the traditional principles of

aeronautical engineering; however, the older points of view are

useful for critical theoretical analysis and empirical

testing.

Before UFO's were ever seen and validly reported, Townsend Brown

developed a captive flying saucer - a scale model saucer with a

free bearing going around a stationary pole.

Brown did not start with round objects, in fact, the first object

that he flew was a triangle, the next a square, then a square

with the edges cut off, and finally a round shaped saucer.

Eventually, experiments proved the saucer shape most effective.

Changes were made for empirical reasons.

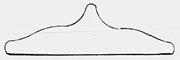

Having solved the problem of horizontal thrust, Townsend Brown

developed a profile shape which would be most efficient to

navigate the electrogravitational field for maximum vertical

thrust. The final profile that developed was the shape

illustrated here:

The first report of a disc-shaped object in the sky dates back to

the sixteenth century. At long intervals during the centuries

since then have come other reports. Most of them are undoubtedly

unreliable as observations, distorted by telling and retelling.

But in these older reports, as well as in the very numerous

series which has accumulated since 1947, there is a teasing

common thread concerning appearance and behavior which makes any

certainties about the unreality of flying saucers very

insecure.

One of the great difficulties in substantiation of these reports

is that, in both appearances and behavior, these objects seem to

be simple scientific impossibilities. Here are some of the

reasons advanced by technical men to prove the impossibility of

devices such as the reports describe:

These are weighty arguments PROVIDED THE ASSUMPTIONS BEHIND THEM

ARE CORRECT. As I have previously indicated, the observed motion

of condenser has been labeled the Biefield-Brown effect.

Studying this effect, Brown pointed out in 1923 that this

tendency of a charged condenser to move might easily grow into a

new and basically different method of propulsion.

By 1926 he had described a "space car" utilizing this new

principle.

By 1928 he had built working models of a boat propelled in this

manner.

By 1938 he had shown that his specially designed condensers not

only moved, but had certain interesting effects on plants and

animals.

All of this, while very exciting, is for most of us just a

repetition and reinforcement of the rapid scientific development

so characteristic of our age. But then came the unexpected

Townsend Brown, working in his laboratory, building models and

trying endless variations in size, shape and design of his

charged condensers, made a flying saucer which flew around a

maypole, before flying saucers became a newspaper topic. And the

reasons listed above, which led the specialists to reject the

reports of observed saucers, proved to be both explicable and

necessary to their operation under the electrogravitational

principle.

Let us look at the four main objectives in a new light:

The reasons advanced by the experts to "explain away" the saucer

reports, when seen from a new and different viewpoint appear to

be the specific reasons why they can operate, on

electrogravitational rather than electromagnetic principles.

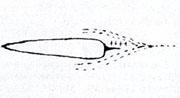

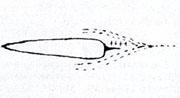

The next opinion which must be corrected is the idea of overly

intensified supersonic vibration. The Townsend Brown experiments

indicate that the positive field which is traveling in front of

the saucer acts as a buffer wing which starts moving the air out

of the way. This immaterial electrogravitational field acts as an

entering wedge which softens the supersonic barrier, thus

allowing the material leading edge to enter into a softened

pressure area. Diagramed, this would be illustrated as

follows:

It should be noted that in a jet plane or guided missile the

extra weight added to create the Biefield-Brown

electrogravitational effect would be compensated for by the added

thrust created by the movement of the plane toward the positive

field created in front of the leading edge.

As we have previously stated, for every known electromagnetic

effect there is an analogous electrogravitational effect but

electrogravitational applications and results differ from those

of electromagnetic. This presupposes that an entire new

electrogravitational industry comparable to the present

electromagnetic industry will emerge from the theoretical

formulations and empirical experiments of Townsend Brown.